Czechoslovakia Expedition 1991Following the dissolution of the eastern block over the last year or so exciting new karst areas have now been opened to the average British caver. One such area is located in the south of Czechoslovakia, an area known as Moravia, and it was in this area that most of our activities were centred. This small area of karst (approximately 2.5 miles wide and 15 miles long) is found to the north of the large industrial town of Brno and consists of several plateaus dissected by valleys and canyons reaching 450 feet deep. The whole karst area has been designated a national park and its numerous show caves and gorges attract Czechs in their thousands during the holiday season. Travel

Due to the amount of equipment needed on a caving expedition the only feasible method of transport is van. We found that a twelve seat minibus would just about cope with eight people plus equipment although seven people would probably be preferable. The journey itself is in excess of 1,200 miles travelling through Belgium and Germany before crossing the Czechoslovakian border. The drive can either be blitzed, as we did, by utilising early ferry crossings in a day and a half or, if time allows, a more leisurely two day drive is probably beneficial for moral. Nearly all the journey is along good dual carriageway and motorway with plenty of services and restaurants en route. Border crossings in Western Europe obviously present no problem but we were expecting a little more trouble from the Eastern frontier. Our fears, however, were unfounded and we were asked for our passports more out of curiosity than concern. A useful ploy for escaping search seems to be for the whole van to feign deep sleep ( apart from the driver). This causes such confusion among the customs officers trying to identify everyone that passports are stamped blind and the van is waved through at dOuble speed. There remains some confusion over the purchase of petrol once in Czechoslovakia. The old communist system insisted that all foreigners bought petrol coupons from the national banks (an extremely long and boring paper wasting exercise) and presented them to a garage in exchange for a certain amount of fuel. We were later told that this system no longer applies and that anyone (national or foreign) can purchase petrol using local currency. The garages were as confused as our guides and we found that the easiest way was to simply fill the van up and argue very loudly in English. After five minutes, with the petrol queues gradually growing, we found that all garages were willing to accept cash. We would recommend buying as little fuel as possible when in Czechoslovakia (fill up in Germany) as the petrol is of a much lower grade than in the west and this certainly affected the van's performance. Food and accommodationWe had arranged with our guides to spend our first week exploring the small cave systems near Prague before travelling south to the ma in caving area of Moravia. Unfortunately our guide for the first week was stranded in Italy after his car broke down en route home from an international caving convention. This, however, presented no problems for our rather generous reception committee who promptly gave us a front door key to the empty house and told us to treat the place as home. This was the kind of warm welcome we were to receive wherever we travelled in Czechoslovakia. The house we stayed in was in one of the nicer areas of Prague but was still incredibly small with three tiny rooms a kitchen and a bathroom. Conditions were cramped enough for the eight of us without our host reappearing with his wife and two children. There is no shortage of food in Prague although it is far more expensive than elsewhere in Czechoslovakia. The night before we left for Moravia we ate a five course meal at one of Prague's finest restaurants at a cost of around eight pounds per head, although meals can be bought at any of the local hostelries for between one and two pounds per head. Once outside Prague the situation changes, with food becoming scarcer but also a lot cheaper. If you are travelling through small villages in a large group expect to split into smaller groups as it appears that most pubs only have enough food for three or four people. If you are lucky enough to get an inn to serve the whole group then be prepared for extremely small portions and a menu change at very short notice. The staple diet generally consists of meat or fish served with dumplings (knedlik) and pickled vegetables. As noted above the portions are small and the scarcity of food means that it is unlikely you will be able to order a second portion. On arrival in Moravia we spent the night in the apartments of our hosts in Brno. It was here we were to meet our only real stumbling block. In our letters to and from the Czech Speleological Society we arranged a reciprocal trip with our counterparts travelling to Somerset to cave with us the following year. On arrival in Brno we were to find that the club who were taking us caving did not wish to participate in an exchange trip but were more keen to raise funds for their next expedition to Greece. On learning this we entered into negotiations and, after quite some time, agreed that a donation of two hundred pounds was agreeable all round and that there would be no exchange trip the following year. This is, apparently, a recurring problem experienced by a few visiting UK clubs. Our only advice is to keep negotiations friendly as any early correspondence is passed through a central contact in Prague and it would appear different promises are made to both parties involved. Czech Speleological SocietyCzechoslovakian caving is split into two geographical areas the western Czech half which was the area we visited and the Eastern Slovakian half. All the caves we visited were locked and indications are that the same policy is adopted all over the country. The simple fact is that unless you have an official guide caving in Czechoslovakia is impossible. Within the C.S.S. there are a number of local clubs which are all allotted an area of land. These clubs are allowed to explore their own patch as much as they like but under no circumstances are they allowed to visit areas belonging to other clubs. Exploration on another club's land is not tolerated and any individuals caught are expelled from the C.S.S. a move which, in effect, means that they can no longer cave. Because of these jealously guarded boundaries there appears to be very little co-ordination on a national scale and all available time seems to be spent blowing up the countryside to try and find new passageway. The ridiculous allocation system was highlighted to us when we visited a club which had spent twelve years cheerfully blasting its way into a mountain. Our guide explained that the blasting continued because this particular club had no caves on its territory and, what's more, it did not expect to find any. It was no surprise to us that when we enquired as to the possibilities of a digging trip the conversation was rapidly changed to pubs and whether or not we would like another beer (a line we always seemed to be falling for). On one occasion we were taken to a swallet where a definite waterfall could be heard underneath a small pile of boulders. As soon as we moved to investigate the choke we were physically restrained by our hosts who later explained that we were not on their club's territory and so could not dig. The fact that Czech caving is so closed was disappointing to all of us. It must be said that the possibilities of exploration or caving as a group without a guide is nil. Even so there are some caves worth seeing and the friendly nature of the local cavers makes it a good destination for an informal visit. Carlsteyne CaveThe largest cave in Western Bohemia, Carlsteyne Cave lies a few miles outside Prague in a large disused quarry which now doubles as a climbing and abseiling face. The entrance to the system is a small hole about eight feet up the rock face. This small phreatic tube divides almost immediately, the right hand fork leads into a small chamber with a stemple assisted awkward descent. On entry into the chamber our guide informed us that this was in fact a dead end and the way on was via the left hand fork. The same man had previously told us we would only need shorts and a tee shirt for this walk through cave. Strange sense of humour these Czechs! The cave continues along phreatic tubes before entering a ten foot flat out squeeze which definitely does not suit the larger caver. The cave then changes dramatically to the sort of sharply inclined rifts that love to eat oversuits and furries. The rifts occasionally break into large chambers and in one such chamber lies possibly the most unusual sight in Czechoslovakia. A short hands and knees crawl leads to a smaller chamber in the centre of which lies a large rock table which is covered in hundreds of clay statuette figures. Our guide explained that the hands and knees crawl was once a much tighter squeeze and that it was here in the small chamber that anti-communists met together in relative freedom. It appears that word was leaked to the local police who entered the cave mob-handed and blew their way into the chamber before smashing everything in sight. From here the cave carries on much the same as before with lots of inclined rifts interspersed with a few larger chambers and is vaguely reminiscent of Eastwater Cavern. Rudicke Propadani Cave This was to be our first cave in the Moravian area and turned out to be quite an eye opener in more ways than one. The system was discovered in the early part of the nineteenth century and is now the centre of activity for the Rudice Caving Group. The old wet entrance, beginning at the swallow hole of the Jedovnikcy potok creek, consists of several extremely wet waterfall steps some 270 feet deep which can freeze in winter making an interesting icy descent. A newer entrance has, however, been opened and this is impressively lined by thick concrete piping. The descent is a steep one down fixed ladders which are, for the most part, reasonably safe. It was here that we learnt that due to the shortage of funds available for caving all the caves in the area have fixed aids and that these aids are replaced as soon as an accident occurs. Lifelining is a virtually unheard of practice due to the stability of the ladders (or lack of money) so there was a good deal of trepidation as one by one we started the 300 foot descent to the large cathedral shaped Hugo's Dome where an impressive surge of active water on the left indicated a link up with the alternative wet entrance. From the dome the stream is followed along its course via an ingenious but totally unnecessary system of wire traverses designed to keep the average Czech caver dry (we were later to be amazed at the lengths gone to to achieve totally dry caving). It was soon found that strolling down the knee deep stream was far easier and more comfortable than daring the rather ominous traverses. The passage continues with impressive dimensions (in places 480 feet high) and takes in several subterranean tributaries, one of which serves as the main water supply for the nearby village of Rudice. After a pleasant stroll we encountered what must surely be one of the most unique features in Czechoslovakia. A small tributary enters from the roof forming a huge 20 foot dripstone column of pure white with several very impressive gour pools. Leaning against this column is an old wooden ladder originally used for explorations in the early twentieth century but which is now encrusted in the same pure white calcite. It was at this point that we first noticed, with a certain amount of dismay, that little, if any, care or consideration is given to many of the formations throughout the area. The gour pools which most British cavers would circumvent with great care were treated merely as another obstacle by our hosts whose main preoccupation seemed to be exploration (a view which was emphasised more and more with every trip). After this impressive spectacle the roof drops dramatically and the rest of the cave is mainly a hands and knees crawl in low water (although the water level can rise dramatically) on a gravelly floor along some well formed phreatic passageways. The system ends for the non diver at the srbsky sump and comprises about 3.5 miles of passageway. An interesting through trip is now available via a 500 foot shaft (making it the deepest vertical cave in Bohemia) which has recently been dug out. Byci Skala CaveThis cave, found at the rising of the Jedovnikcy potok creek, was originally of great archeological interest because it contained the skeletons of some forty people as well as two ritual cremation altars. The fact that most of the skeletons found were women who bore traces of a violent death led local archeologists to believe that they were slaves who were killed and cremated along with their owner. In the Second World War, the large entrance leading to a vast chamber meant that it was an ideal base for the German army, who used it as a munitions factory. Because of the military usage all of the drier parts of the cave are reasonably well lit. An extremely modified passage (not the last we were to see) takes the caver in a short while to the edge of the streamway where a boat can be taken to the first sump (Driny sump). Diving of the Driny sump (started at the turn of the century) has eventually led to the discovery of two new dry systems (Prolomena Skala and Proplavana Skala) in 1984. The initial discovery was quickly followed up in 1985 by the first trip through the downstream end of the Srbsky sump thus connecting the systems to Rudicke Propadani and making the second longest system in Bohemia with passages covering over 7.5 miles. Amaterska Jeskyne Cave This is by far the largest cave system in Bohemia containing over 15 miles of passageway and its resurgence in the huge Macocha gorge has to be the most breathtaking sight in Moravia. The entrance to the system lies in a shakehole at the top of a hill which was dug for several years before the final breakthrough in 1969. Finding this entrance proved to be a little difficult as our guide explained that he had not visited the cave for over twenty years. Having found the entrance the next problem proved to be moving the huge plate steel padlocked cover. There was a strong feeling of deja vu as we scaled the fixed ladders down the entrance pitches which are in excess of 120 feet. A small hastily erected cat-walk has been laid down across the Hall of Kings. This, unfortunately, has been installed about twenty years too late and all that remains of the once well decorated chamber are half a dozen large columns. Such is the state of disrepair that it was several minutes before we realised that we were all walking over a calcified slope which, when discovered, would have been of the purest white. A couple more small fixed ladders lead down to the active streamway where, to our delight, we found two small inflated dinghies, and, to our dismay, more of the same ruined formations. A quick trip through part of the upper series showed some more of the well formed phreatic tubes and then we dropped back down to the dinghies for further exploration of the active river system. The dinghies are dragged for the first few yards before the water becomes deep enough for them to float. Having successfully got on the boats (two people per boat) one man paddled from the back while the other was able to pull and guide the boat using a very clever line suspended from the roof of the cave and passed through numerous eyebolts. The boats are completely superfluous to the wetsuited caver as the streamway is very similar to the ducks and creeps in Swildons 2 with a low arched roof and gravelly floor but they do add a new and different dimension to caving as well as being extremely good fun. After a few hundred yards the canal once again becomes too shallow for the boats and the way on is via a hands and knees crawl which eventually lowers to a flat out crawl in a small stream ( although our guide miraculously managed to stay dry). After a short crawl a chamber is entered and the way on is barred by an armpit deep streamway. It was at this point that our guide tried to tell us that we had arrived at the sump although the passageway could clearly be seen beyond. The stream can indeed be waded (although our guide managed to find a dry traverse after half an hour) and the passage continues along more low streamway crawls interspersed with small chambers for a considerable amount of time with no end in sight. In one chamber unusual 'leopard skin stalactites' ( an effect caused by the deposit of dried mud rings all over the surface) can be seen as well as some better preserved formations presumably due to the isolation of the further reaches of the system. On the return the only remaining obstacle to be found is the extremely heavy and obstinate lid which requires three men perched on top of each other swearing very loudly before it will finally open. Macocha Gorge and Punkva CavesThe Macocha gorge is situated on a wooded plateau between the Suchy and Pusty zleb valleys along with several small caves. The gorge, some 530 feet deep, is the remains of a huge chamber whose ceiling collapsed and is, we were told, a popular spot for suicide attempts. Two observation points, one at the top and the other half way down, would provide any would be abseiler with ideal take off points for a breathtaking descent. There are two other ways to the bottom of the gorge. One involves a 1,300 foot dive through from the recently connected Amaterska cave while the other easier route is a walk through the Punkva caves which are reputedly the most impressive show caves in central Europe. The formations certainly are impressive, particularly the ones taken from several nearby caves which were too small to allow visitors. This formation stealing seems prevalent in all the large show caves of the area and is sad proof of the lack of awareness local cavers show. The highlight of the trip is definitely the boat trip back from the bottom of the gorge to the entrance via the wonderful Fairytale Dome Chamber. This is beautiful, unspoilt passageway and you can only wonder what other caves in the area may have been like when discovered. Although only a show cave the Punkva system really is a must for any itinerary, a prime example of both the positive and negative aspects of cave conservation for money. Caving on the Macocha plateauThe area surrounding the Macocha Gorge is pitted with small cave systems most of which are fairly vertical although the fitting of fixed ladders means that no SRT equipment is required. We spent the afternoon exploring three of these smaller systems, the deepest of which is about 1,300 feet, one of the three deepest systems in Moravia. The cave ends in a most impressive 120 foot fixed ladder pitch down into the middle of an immense chamber. The fixed ladder certainly seemed solid but, in hindsight, the lifeline we were told we did not need would probably have been useful. There is nothing of any great note in these systems except for the architecture around the entrances which shows some ingenuity and the rather suspect state of a lot of fixed ladders, some with rungs missing others with fixings which allow the ladder to tip backwards alarmingly and even one or two completely unfixed. It was in one of these systems that we experienced our first nylon ladder - a wonderful mixture of laddering and bunjy roping. This particular ladder had a stretch ratio of roughly twenty per cent and even our guide conceded that a lifeline would probably be prudent - the only time we were to use our rope on the trip. Caves around the Punkva SystemA number of small, well decorated, dry systems are to be found in the valley at the bottom of the Gorge around the entrance to the Punkva show caves. These small horizontal systems can provide a day's worth of entertainment with no sign of any fixed aids. The first system entered was via a fairly hairy scramble thirty or forty foot up the canyon wall and consisted of a single low crawlway interspersed with two or three very draughty chambers and a reasonably tight squeeze. Most of the cave is littered with the remains of formations long since removed .and taken to local show caves, although the further reaches of the system still have some formations and a camera is definitely worth taking. One of the other systems visited owes its existence to the old Czech government and some bloody-minded determination. Determined to find a dry route into Amaterska Cave the government started blasting their way into the canyon wall. The passageway was made extremely large, approximately 10 foot by 8 foot, so that the spoil could be removed easily by train. The blasting was abandoned when the miners broke through into a minor cave system which ended in an extremely well decorated chamber and high aven after only a few hundred yards. Single rope techniqueSRT is really in its infancy in Czech as the cost of equipment means the average caver cannot afford it. On our trip we were assured that our rope was unnecessary and that our guide would provide all the rigging aids required. We were more than a little surprised when he turned up with an apparently lightweight kit bag but he reassured us that all would be okay. On arrival at the cave entrance, typically surrounded by four foot high nettles, the inevitable ten minute unlocking ceremony was eventually completed to unveil a vertical shaft piped for the first ten foot. The most disturbing sight, however, was that of a rope descending into the darkness with only a single snap gate karabiner for rigging. Our guide promptly proceeded to load up and commence abseiling down the rope with a cheery grin. After some hasty alterations to the rigging so that we at least had a back up anchor point we proceeded down the rope very cautiously, noting the rather thick coating of mud on the sheath. The first deviation was reached after dropping about thirty foot and was attached via an extremely old piece of hemp rope which had presumably remained in situ since the cave had been rigged. After passing the deviation another twenty or thirty foot descent led to a second, equally dodgy deviation. It was at this point that common sense overtook our desire to explore and we decided that the best move was up. We then had an interesting ten minute discussion with our non-English speaking guide who at first could not grasp what we were saying and then could not understand our concern. After all, explained his friend later, no one had had an accident on the rope or it would have been replaced. From these experiences we would obviously recommend that all the caves visited are rigged by the visiting party. Fixed ropes are obviously not a good idea although costs are so high that local clubs simply cannot afford a store. Not only would self rigging be safer but it would also teach the local Czech cavers correct rigging practices and so, in the long term, would prove beneficial to all parties concerned. back to index of foreign trips

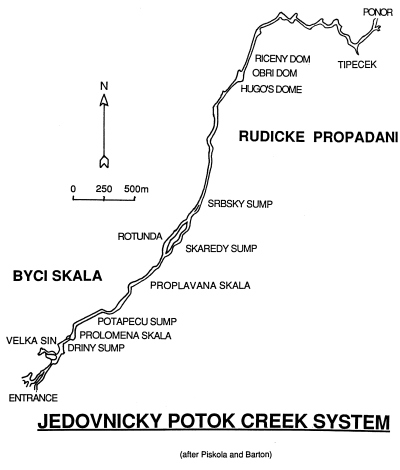

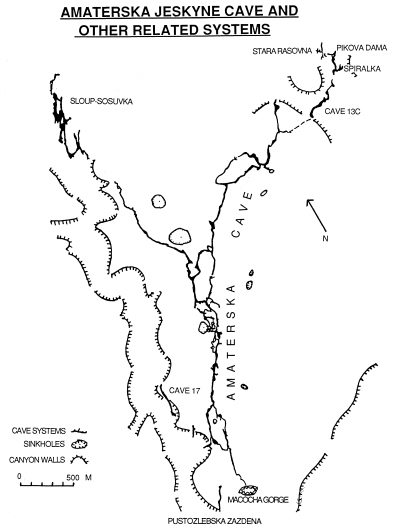

Mendip Caving Group. UK Charity Number 270088. The object of the Group is, for the benefit of the public, the furtherance of all aspects of the exploration, scientific study and conservation of caves and related features. Membership shall be open to anyone over the age of 18 years with an interest in the objects of the Group. |